Posters advertising Chung Ling Soo‘s performance at The Palace (Bristol, UK), circa 1910.

Before the times of the internet, radio and television, advertisement was done with the help of what we call “posters,” placards and bills that were posted on walls to inform the passer-by of events or products. Theatre shows, plays and indeed also magic shows were thus advertised. Most of the posters before 1870 were textual or just printed with black ink: it was with the perfection of colour lithography that economical, mass production of colour posters became available. Between posters advertising products or political ideas, those relating to entertainment were a common fixture on city walls and every theatre printed posters weekly to try to entice the paying public to the show.

Magicians, especially travelling ones, had been using posters for generations: many travelled with their own printing blocks and had new posters created in every city where they managed to give one or more performances. With the advent of lithography, magicians started to make good use of the technology to produce colourful images, with which to plaster walls, as it can be seen in the photo above, announcing a week’s performance of (fake) Chinese magician Chung Ling Soo in Bristol, showing 31 different pictorial posters (and two with the week’s “bill” at the theatre). These were only a small part of the posters used by Chung Ling Soo…

A relatively large number of posters of magicians and for magic shows survive and many are sought after by collectors, some of whom have created amazing collections: among them, those who have made part of their collection available on the web are Norm Nielsen, Kenneth Trombly and Charles Greene III. Their collections are amazing and what they show on the web is only a small part. All these gentlemen are expert in the field of magic posters collection and very generous with their expertise.

I cannot consider myself a poster collector: I have a few dozen magic posters, most of them in storage, and my posters are either “contemporary” (of magicians from the 1950s onward), or generally common ones. Yes, I have the odd Chung Ling Soo poster, or a common Carter “World’s Weird Wonderful Wizard”, in addition to some well known Alexander “The Man Who Knows” poster, or some Roody, Carl Germain, Sorcar, etc. I have already spoken of my playbills of Linga Singh in a previous post. A few posters of Italian illusionist Amedeo Majeroni are in my collection, too, and they may be discussed in a future article. Of course I have a substantial number of posters of Chefalo, my main interest. But, still, not as many posters as some of other collectors, and only a few posters are really exciting or unique.

To be able to collect posters, one needs sufficient wall space to properly enjoy them: there is little joy in looking at many tubes, each containing one or more posters worth a few thousand dollars or pounds, and not seeing them on walls. Magic posters don’t come cheap either: at least, not antique magic posters. When I started to collect magic posters, I concentrated on contemporary performers (I think I have an almost complete collection of Italy’s Silvan posters, for example): in a few years, they will be classified as “antiques”. I still enjoy collecting magic posters and I am always on the lookout for unusual ones, especially if they are about Italian magicians, or have a connection to Italy.

None of the collectors of magic posters I know has ever been able to accumulate a collection like that of Dr. Hans Sachs (1881-1974), a German Jewish dentist who amassed the largest collection of posters before World War 2. His story can be easily found on the internet, but it is worth telling again. Dr. Sachs began to collect posters in 1895, attracted by the beauty of what was considered a lesser form of graphical art. His hobby slowly turned into a passion and, in 1910, Dr. Sachs founded the first international poster society, the Verein der Plakat Freunde and started to publish the magazine Das Plakat, which documented the posters of the era. Dr. Sachs was not collecting “magic” posters: every pictorial poster, whatever its subject, was added to his collection. If the poster happened to advertise a conjurer or a magic show, then it could have been added: the subject of the poster was not important to Dr. Sachs, unlike to magic poster collectors.

By 1938, Dr. Sachs had in his possession more than 12,500 posters, the largest and most significant poster collection in the world at that time. These posters were often displayed publicly in exhibits in the 1920s and ’30s. The collection included every kind of poster: from bicycles to cars, from soap to drinks, from political to theatrical, from all over Europe and the USA, and beyond. Dr. Sachs had a small number of posters of magicians, or of magic shows, a tiny proportion in this behemoth collection. But he was living in the wrong place… In the 1930s, Hitler had placed a ban on “degenerate art”: the artistic works that opposed his vision of beauty and reality. Some of the posters in Dr. Sachs’ collection fell into this category.

This served as a pretence to Joseph Goebbels, chief of Nazi propaganda, to send police to Sachs’ home to confiscate the entire collection. While Goebbels wanted the collection for himself, the police told Sachs the posters would be transferred to a new museum, where they could be cared for and preserved. Many years later, Sachs himself reported the experience:

The day after next, three giant trucks appeared. The blackest day of my life had begun. With my own hands, I took 250 aluminum arms, each containing 50 posters, from their supports, removed the bibliography with its 80 larger works and hundreds of single articles, carried 12 full card indexes boxes with 1,000 cards each and the entire miniature graphic to the trucks, where they were carried off – never to be seen again.

Sachs, a Jew, was arrested on 9 November 1938, on what will be known as Kristallnacht, and sent to the Sachsenhausen concentration camp near Berlin, from which he managed to escape and, eventually, flee to America. He was told his beloved collection had been destroyed. If you are a collector, I am sure you can understand the pain and the grief of having your collection snatched away, and to learn, or even just suspect, that your collection has now been destroyed. The anguish must be unbearable, especially as Dr. Sachs had seen first hand the campaign of books burning carried out by the German Student Union in 1933, and he knew that his posters could have shared the same fate.

However, there was a lingering suspicion that the collection still existed: in the mid-1960s, some posters began to surface in East Berlin, being sold at auction and privately, and a long battle from Dr. Sachs’ son, Peter, began. Peter Sachs was trying to locate the posters and to have them returned to the family. What it transpired, after a long legal battle that lasted more than 30 years, is that some of the posters, about 8,000, had at some point being held in the German Historical Museum, in what was the Russian part of Berlin after the war. What it seems is that the Soviets had seized the collection at the end of the war, and stored it (or part of it) there. Eventually, 4,259 posters were returned to the family in 2013: about 30% of the original collection: a small breadcrumb of a once vast collection.

Some posters were donated to museums, a handful kept by the family, and the rest auctioned off, allowing contemporary collectors and institutions to care for what are, in many cases, the only surviving records of an artistic artefact of a time gone by.

One of the posters in Dr. Sachs’ collection depicts Italian actor, magician and quick-change artist, Leopoldo Fregoli (1867-1936), and is dated from 1911. This was the period of highest fame and success of Fregoli, during his season at the Olympia in Paris where his booking was extended to last more than one year, with a great success of public and critics. Fregoli had invented a new kind of performance, one that involved rapid changes of costumes that allowed the single performer to impersonate all characters in a play. His ability as an actor allowed him to change personality as well as costumes, giving the illusion that more than one performer was part of the act. Fregoli was also an accomplished conjurer and used regularly magical techniques in his performances and his transformations often borrowed from magical principles to operate. While not a “pure” illusionist, Fregoli has certainly a place in the history of theatrical magic.

In 1911, he had a nice poster, until now practically unknown among magic collectors, drawn by Italian illustrator Romeo Marchetti (1876-1940), well known for his satirical illustrations in magazines, and for theatrical and operatic posters. A copy of that poster, printed by Pilade Rocco (a printer of posters and postcards in Milan, Italy) was among the 4,000 surviving posters of Dr. Sachs:

Fregoli, by Marchetti, from the Hans Sachs collection. Now in the Marco Pusterla collection

(click to enlarge)

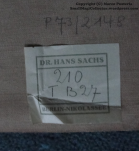

The poster had been mounted by Dr. Sachs on a flimsy backing and it had a small bit missing at one side that has been covered with some paper (a primitive form of restoration). On the back, there is a label indicating the provenance from the Dr. Sachs collection (see image at the side) and some numbers pencilled in: certainly some cataloguing coding. The colours are more vibrant than what they look in the photo: the black is uniform and the face, particularly, looks like it has been hand-painted rather than printed. The text is more of a silver colour rather than the white from the photo. The top right corner is not missing: it was folded when the photo was taken. The poster size is circa 97 x 67 cm (38.2 x 26.4 in).

This poster, with a long and chequered history, is now in the Marco Pusterla collection. It doesn’t show any magic per se, but shows an Italian magician and one of the greatest artistes of the turn of the century, somebody whose name is now synonym for transformations and used as a medical term.

The film below, a short documentary from Italian television about the history of quick-change, shows some rare films of Fregoli, followed by some scene about his career by Italian actor Alberto Sordi and, finally, by the contemporary heir of Fregoli: Italian Arturo Brachetti who has brought Fregoli’s skills to the top possible levels:

While I originally thought this poster may be unique, it seems this is not the only copy of it: at the side you can see a small photo, in very low resolution, of a copy of the same poster, with an illegible overprint of probably a place where Fregoli performed at some time. That copy seems to have been trimmed along the right hand side, but it’s difficult to say without seeing the original artefact. It is not known where this copy resides now, or if the poster still exists: apparently, the image was taken from a book (click on the image for further information). A fellow collector has also seen the same image used on a handbill that had, on the opposite side, a photo of Fregoli in one of his costumes. Fregoli retired from the stage in 1925, fourteen years after this poster was produced, and died in Viareggio, Italy, in 1936, two years (almost to the date) before the arrest of Dr. Sachs in Germany.

While I originally thought this poster may be unique, it seems this is not the only copy of it: at the side you can see a small photo, in very low resolution, of a copy of the same poster, with an illegible overprint of probably a place where Fregoli performed at some time. That copy seems to have been trimmed along the right hand side, but it’s difficult to say without seeing the original artefact. It is not known where this copy resides now, or if the poster still exists: apparently, the image was taken from a book (click on the image for further information). A fellow collector has also seen the same image used on a handbill that had, on the opposite side, a photo of Fregoli in one of his costumes. Fregoli retired from the stage in 1925, fourteen years after this poster was produced, and died in Viareggio, Italy, in 1936, two years (almost to the date) before the arrest of Dr. Sachs in Germany.

With a glass of Cognac in my hand, I stand in front of this poster and think about its history. Dr. Hans Sachs collected more than 12,000 posters, of which only a few more than 4,000 have survived pillaging and the war. Of these surviving posters, only a few depicted a magical subject, and even less were about Italian conjurers. It is a lucky combination of fate that allowed the survival of this Fregoli poster that now, more than 100 years since it was printed, graces the walls in my drawing room. Hopefully, the poster will now be recorded and will be safe for years to come: it has survived the delusions of grandeur of a crazed Nazi propagandist, and it now deserves to be protected for future generations. This poster should be the stark reminder of a passion that was crushed by a dream of omnipotence: its survival will now fuel the same passion in the heart of other men.

With a glass of Cognac in my hand, I stand in front of this poster and think about its history. Dr. Hans Sachs collected more than 12,000 posters, of which only a few more than 4,000 have survived pillaging and the war. Of these surviving posters, only a few depicted a magical subject, and even less were about Italian conjurers. It is a lucky combination of fate that allowed the survival of this Fregoli poster that now, more than 100 years since it was printed, graces the walls in my drawing room. Hopefully, the poster will now be recorded and will be safe for years to come: it has survived the delusions of grandeur of a crazed Nazi propagandist, and it now deserves to be protected for future generations. This poster should be the stark reminder of a passion that was crushed by a dream of omnipotence: its survival will now fuel the same passion in the heart of other men.

All content is Copyright © 2010-2014 by Marco Pusterla - www.mpmagic.co.uk. All rights reserved.

Related articles

- After Restitution, Nazi-Seized Posters Seek a New Home (itsartlaw.com)

Wonderful story, Marco. And, obviously, wonderful poster! I am glad that it is in your collection.

LikeLike

Congratulations! For every new item you add to your collection, you can enhance it with its history, making it even more interesting, going beyond the actual value of the object itself.

LikeLike

That was both an informative and a moving story. Thanks for sharing! How. Fitting that the Fregoli now will have a good home……..and that part of Dr Sachs collection lives on

LikeLike

[…] you have been following this blog, you may have noticed that my recent posts were on apparatus, on posters and on more substantial items – not really on “ephemeral” objects. Sometimes, to […]

LikeLike

[…] Chung Ling Soo […]

LikeLike

[…] Site: The Ephemeral Collector […]

LikeLike