David Devant producing a rabbit in 1896

The early years of animated pictures were years of invention: a primitive technology was played with – “hacked” if we want to use a modern term – to become more reliable, safer, cheaper, of better quality. The presentation of moving pictures was a great novelty for public entertainment and it will eventually, in slightly more than 20 years from its inception, kill those live performances that had provided light entertainment for all social classes since the mid of the 19th century.

With the invention of motion picture cameras in the 1890s, films, under one minute length, started to be shown by itinerant performers, or used as acts in a variety (vaudeville) programme, in between live performances. The novelty of cinema attracted conjurers to it, from Georges Méliès, the major technical innovator of special effects in the early history of cinema, to various travelling performers who rented or built their own projecting machines to show films, to David Devant, the premier British illusionist of the time and the subject of this article.

Cinema arrives to London

When cinema started to move its first steps, David Devant (David Wighton, 1868-1941) was already an accomplished magician, working with the famous Maskelyne & Cooke company at the Egyptian Hall in London, the original “Temple of Mystery” and one of the main attractions of the capital. Devant became one of the first magicians to realize how moving pictures could be a game changer in public entertainment. In his memories, My Magic Life, published in 1931, Devant recalls his discovery of cinema:

When Lumière brought the first exhibition of animated pictures to London in 1896, I witnessed one of the original representations at the Polytechnic. At once I saw the great possibilities of such a wonderful novelty for the Egyptian Hall.

In 1896, the Lumiére brothers brought their invention around the world, to try to find parties interested in renting their projector and their films. On 20 February 1896 they presented their invention in the Marlborough Hall at the Polytechnic Institute, in front of an audience of 54 people, all of whom had paid a shilling (sixpence if they were member of the Polytechnic) to witness this novelty. The Lumiére brothers remained at the Polytechnic for 16 days, giving the opportunity to Devant to attend the show, and to convince J. N. Maskelyne and his son to accompany him to the next screening, hoping they would rent the projector for their theatre, but:

to my surprise, Mr. Maskelyne gave it as his opinion that it would be only a nine days’ wonder, and was not worth troubling about.

Robert W. Paul

Maskelyne was quite wrong, as we now know that cinema was not a merely a “nine days’ wonder”, and it eventually killed his kind of magic. Devant enquired about renting the apparatus – that, however, had already been rented to the Empire Theatre in London – but the price, £100 per week (about £11,600 in 2017), was too much for Devant to do anything with. And this could have been the end of Devant’s involvement with cinema, were not for one Robert William Paul (1869-1943), the “father” of British cinema who the previous year had built a animated pictures machine based on the Kinetoscope invented by Edison. For a strange twist of fate, the same day the Lumiére brothers presented their machine at the Polytechnic, Paul presented his machine, the Theatrograph, at the Alhambra Theatre. On learning about Paul’s invention, Devant impulsively rushed to the inventor’s office and caught him just on the way out to present his films at a side-show. Paul and Devant struck a deal whereby Devant bought one of Paul’s machines and began to project animated pictures: this activity (which would see Devant build other machines, sell them to Georges Méliès, sell films and cameras in Great Britain, etc.) would keep Devant busy for years and provided a very steady income to the illusionist, who then was not yet partner with Maskelyne.

But having a projector was not enough: unless you had films to show, your investment was a loss, and films, these short, black and white, silent reels, had to be created, or bought. A few enterprising people were producing films: the Lumiére brothers, Georges Méliès, R. W. Paul and also David Devant, and a collaboration between Paul and Devant takes us to the object described in this post.

The Filoscope

In Devant’s memoires we read:

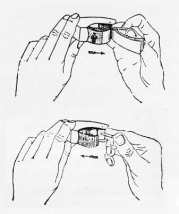

The first animated picture ever taken of a performer was shot by R. W. Paul on the roof of the Alhambra Theatre. It was one of myself doing a short trick with rabbits. I produced one from an opera hat, then made it into twins, all alive and kicking. This picture was reproduced in a little device called a Filiscope [sic]. The hundreds of pictures which go to make up a film of a cinematograph were printed on paper in the form of a little book, the leaves of which were turned one at a time by a simple mechanical device, the rapidly moving leaves giving the effect of movement. This pocket cinematograph sold by the million.

The Alhambra Theatre, London

Devant will do other films with Georges Méliès and will eventually star in a full-length crime film in 1920, The Great London Mystery, a serial. Devant was writing his memoires more than 30 years later, so some of the details are a bit confused, starting from the spelling of the device: it’s a Filoscope. The rabbit production was likely filmed in July 1896 on the roof of the Alhambra Theatre, in Leicester Square, London: the Alhambra was a popular Music Hall and will be demolished in 1936. In its place, there is now (2017) the Odeon Cinema.

The Filoscope

Filoscope was the name used for the patent taken by Englishman Henry W. Short (a friend of Robert W. Paul) for an optical toy where a flip book encased in a metal cover and operated by applying thumb pressure on a lever would produce a sequence of animated pictures. You can see original Filoscopes on Youtube, including a very nice one showing David Devant producing the rabbit from a hat (note that this Filoscope is not in our collection):

The Tom Thumb Filoscope

The Tom Thumb Filoscope, with David Devant and the 1895 Epsom Derby films

In our collection there is a rarer version of a Filoscope, one called the “Tom Thumb Filoscope”. This is basically a tiny flip book, with no mechanical parts at all. It measures 5x5x2 cm and it contains two films: one is the first part of the David Devant one, with the production of a rabbit out of a hat, the second film is a few frames from The Derby, a very early film of the Epsom Derby of 29 May 1895 filmed again by Robert Paul. The photos (frames) of David Devant are 2.5 x 2 cm and are numbered from 2 to 157, but not all frames are present, i.e. not all numbers are. This doesn’t impact the animation: one can still see Devant opening up a collapsible top hat, make a magical gesture over it, put the hand inside and pull out a white, kicking rabbit, which he then gives to an assistant holding a tray.

A second Filoscope is in our collection: this one contains a film of the Gordon Highlanders (92nd Regiment on Foot) marching through a city, and a sequence of one of the first British fiction films ever made: The Soldier’s Courtship, with (then) famous actor Fred Storey. This is another film that was shot by Robert Paul on the roof of the Alhambra Theatre in April 1896, just a few months before David Devant and his rabbits (and you can watch it, almost complete, here. The scene in our Filoscope is only the arrival of the soldier and the embrace: the two actors don’t sit).

Very little is known of the “Tom Thumb” product: who made it, when and what a full collection of these Filoscopes could be. Indeed, at the time of this writing, the only “Tom Thumb Filoscopes” one can find on the internet, are those in our collection, from the sale of a house contents in Suffolk, England. The object may have been produced in the early 1900s and was surely an economical toy to have “animated pictures” in one’s pocket, to show to friends, family and loved ones. I suspect their death rate had to be high, given the ephemeral nature of the object and its small dimensions, not to mention the fragility.

Very little is known of the “Tom Thumb” product: who made it, when and what a full collection of these Filoscopes could be. Indeed, at the time of this writing, the only “Tom Thumb Filoscopes” one can find on the internet, are those in our collection, from the sale of a house contents in Suffolk, England. The object may have been produced in the early 1900s and was surely an economical toy to have “animated pictures” in one’s pocket, to show to friends, family and loved ones. I suspect their death rate had to be high, given the ephemeral nature of the object and its small dimensions, not to mention the fragility.

The film of David Devant is very important for the history of magic, being the first time the most popular magician of the era, and one of the great of all times, was captured on film, but in general these Filoscopes are the silent records of a time when Cinema, that we now take for granted, was being created. And still now, more than 120 years since these photos were taken, we can enjoy the skill and the magic of David Devant.

The film of David Devant is very important for the history of magic, being the first time the most popular magician of the era, and one of the great of all times, was captured on film, but in general these Filoscopes are the silent records of a time when Cinema, that we now take for granted, was being created. And still now, more than 120 years since these photos were taken, we can enjoy the skill and the magic of David Devant.

How long does it take to watch David Devant pull a rabbit out of a hat: when you have the Filoscope in your hands, you can control the speed you release the pages. The viedeo below shows the Filoscope being played, for a full four seconds. Enjoy it!

Very instructive post with one minor correction: Robert Paul actually presented his Theatrographe at the Finsbury Technical College on 20 February, 1896, not the Alhambra Theatre. Paul first performed at the Alhambra Theatre on 25 March, 1896. The flip book that Marco has would appear to be the same as mentioned on this site: https://silentfilm.org/leon-beaulieus-pocket-cinematograph/. As such, it is not unfortunately the Georges Méliès film of Devant which, like The Great London Mystery which featured Devant, no longer seems to exist.

LikeLike

I agree with you. Beaulieu flipbook with David Devant is the R. W. Paul film. Probably a copy from the filoscope Short.

LikeLike